Emma Waugh

Check out my work and reflections in Open Source GIScience!

Uncertainty, Ethics, and Volunteered Geographic Information

November 15, 2021

An analyis of Twitter activity during Hurricane Dorian in 2019 investigated the differences between “Twitter storms” and the real hurricane.

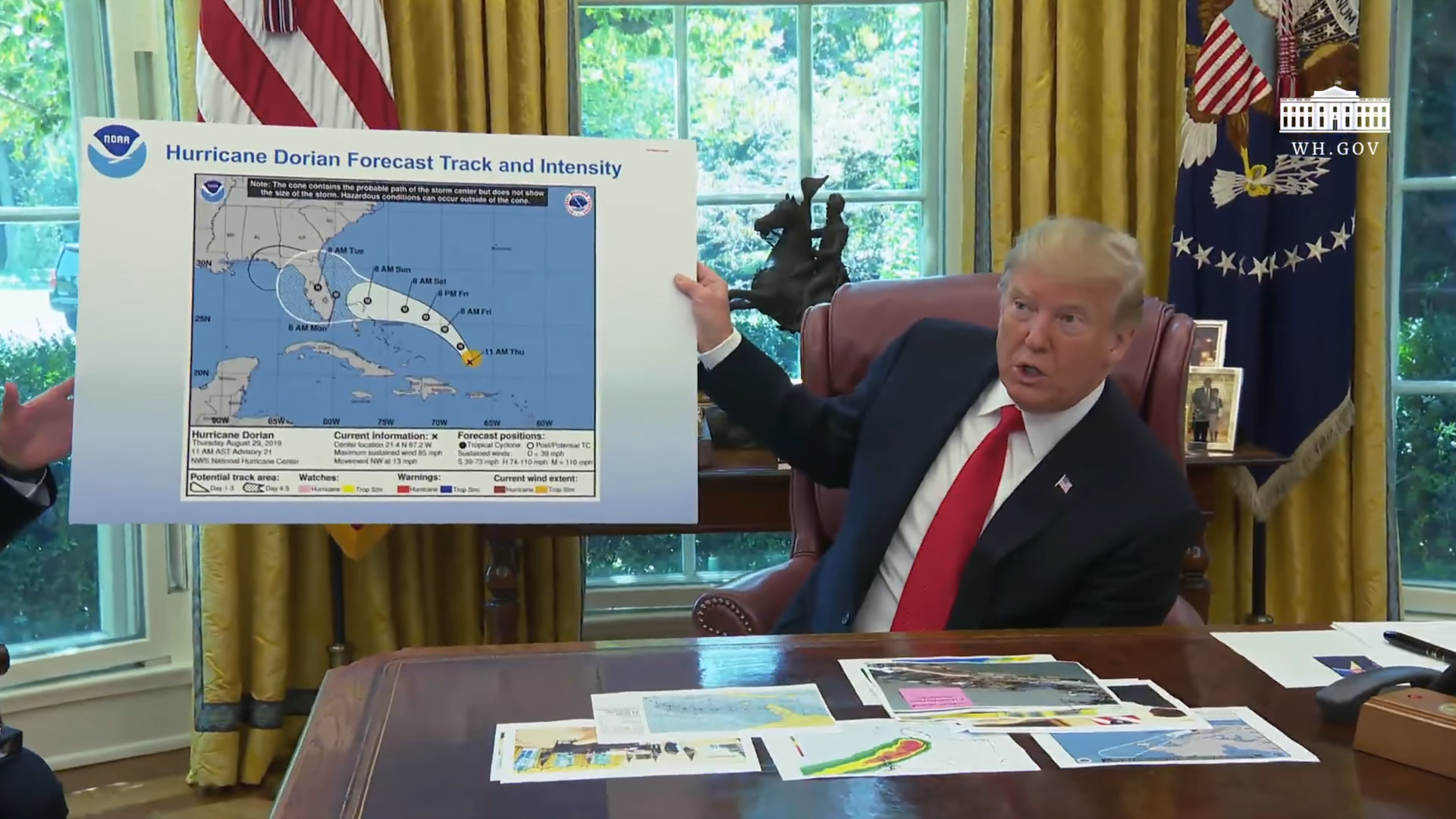

The availability of geocoded tweets allows for tracking tweets around areas impacted by the storm. The analysis also sought to determine the impacts of former President Trump’s addition of Alabama to NOAA’s expected impacted area map, which came to be known as “Sharpiegate.” The search terms “hurricane,” “Dorian,” and “sharpiegate” were used to find hurricane-related tweets during the time period.

While social media data can be an important source of information in the wake of a natural disaster, there are many nuances to its uses, users, and algorithm that should inform the way we analyze and distribute it. Crawford and Finn (2014) write about the limits and challenges to using “crisis data” to respond to disasters. Disaster response and experience is constructed, is “unfolding over a long time, and … popular definitions of disasters produce an ‘emergency imaginary’ that shapes disaster response.” Crawford and Finn are critical of the ways perceptions of disaster are used and misused following natural disasters or humanitarian crises.

Uncertainty in Volunteered Geographic Information

Volunteered geographic information, such as geocoded tweets, inherently include uncertainty, especially through differences in internet access and social media use. To understand the people that are using Twitter, it’s important to understand who isn’t: the subset of the population that uses Twitter to gain and share information is typically younger and more urban than the overall population. Additionally, there are people with lack of internet access or smartphones with geomapping technology, or who are experiencing power outages in the wake of natural hazards like earthquakes, fires, and hurricanes. Additionally, user preferences and the internal algorithm define the types of content people see, engage with, and react to, which can mean that certain dominant “information cascades” are centered while others are sidelined.

Ethics of Volunteered Geographic Information

The use of volunteered geographic information also necessitates an ethical consideration; Crawford and Finn discuss questions of privacy, consent, and agency, some of which complicate the uncertainties named above. Many people are not aware that they are sharing information about their location. So-called “self-managed privacy” leaves room for people to unknowingly agree (or more often, to not actively disagree) to their location being shared. Privacy rights are often renegotiated in a disaster response, as personal locations are used for tracking and rescuing. However, sometimes these boundary adjustments are exploited, as when the Haiti Mission 4636 information was publicized without the agreement of the users (Crawford and Finn).

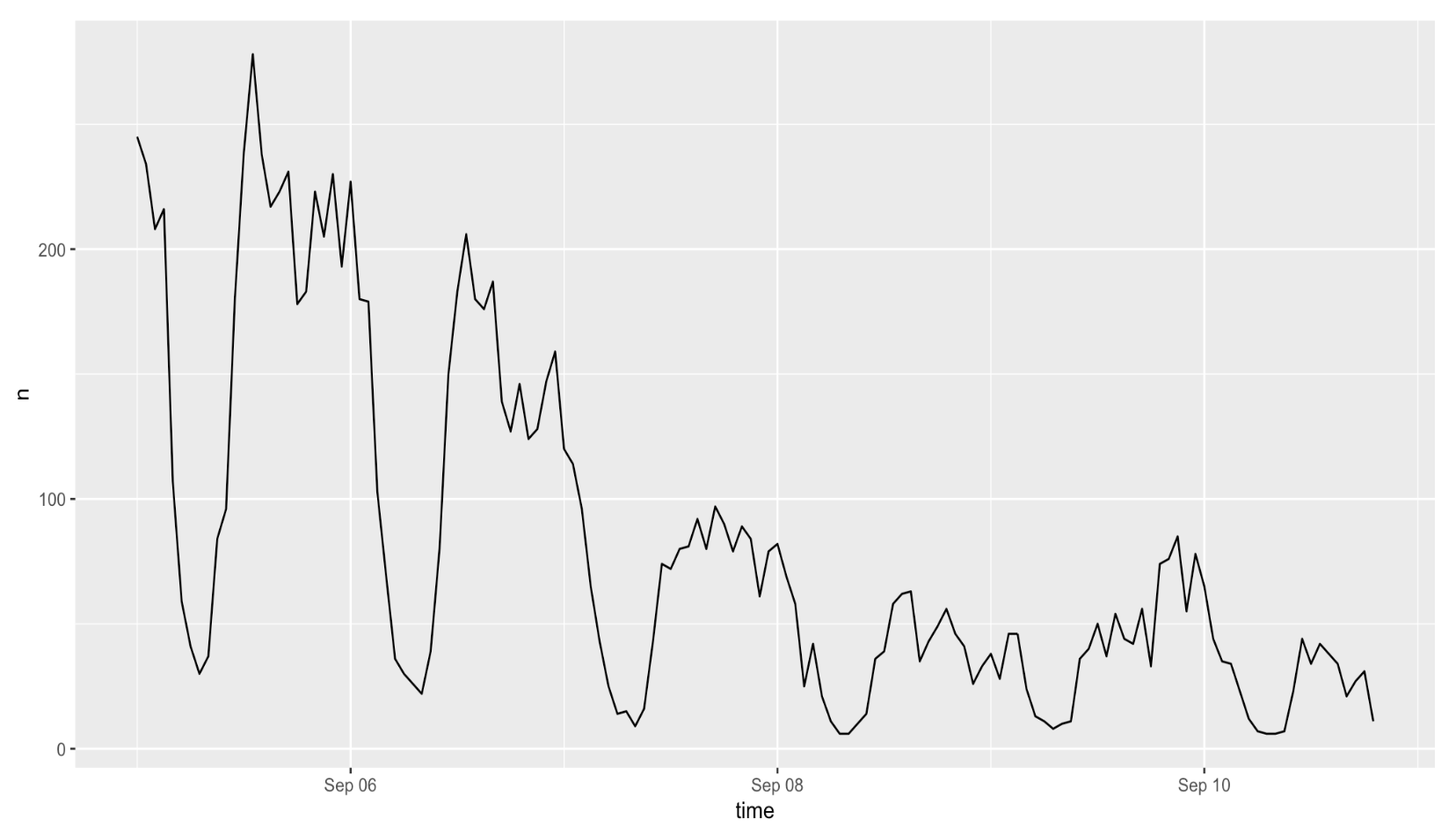

Crawford and Finn also call into question the concept of disaster, as news and social media typically follow them when they are new and sensational (hours-days scale), but neglect to cover the long-term effects (years-decades scale) of these events. These timelines can promote short term attention and solutions to supposedly “isolated events”, giving agency to the humanitarian organizations that intervene rather than the people affected by it. For example, a timeseries of Hurricane Dorian-related Twitter activity shows that activity tanked after a 2-day period (see below figure), even though displacement, damage, and devastation lasted far beyond that.

Volunteered geographic information should definitely still be used in disaster and crisis response, but should only be viewed as a partial representation of the community response at a given time. The affected community must be placed over outside parties in the pursuit of information.

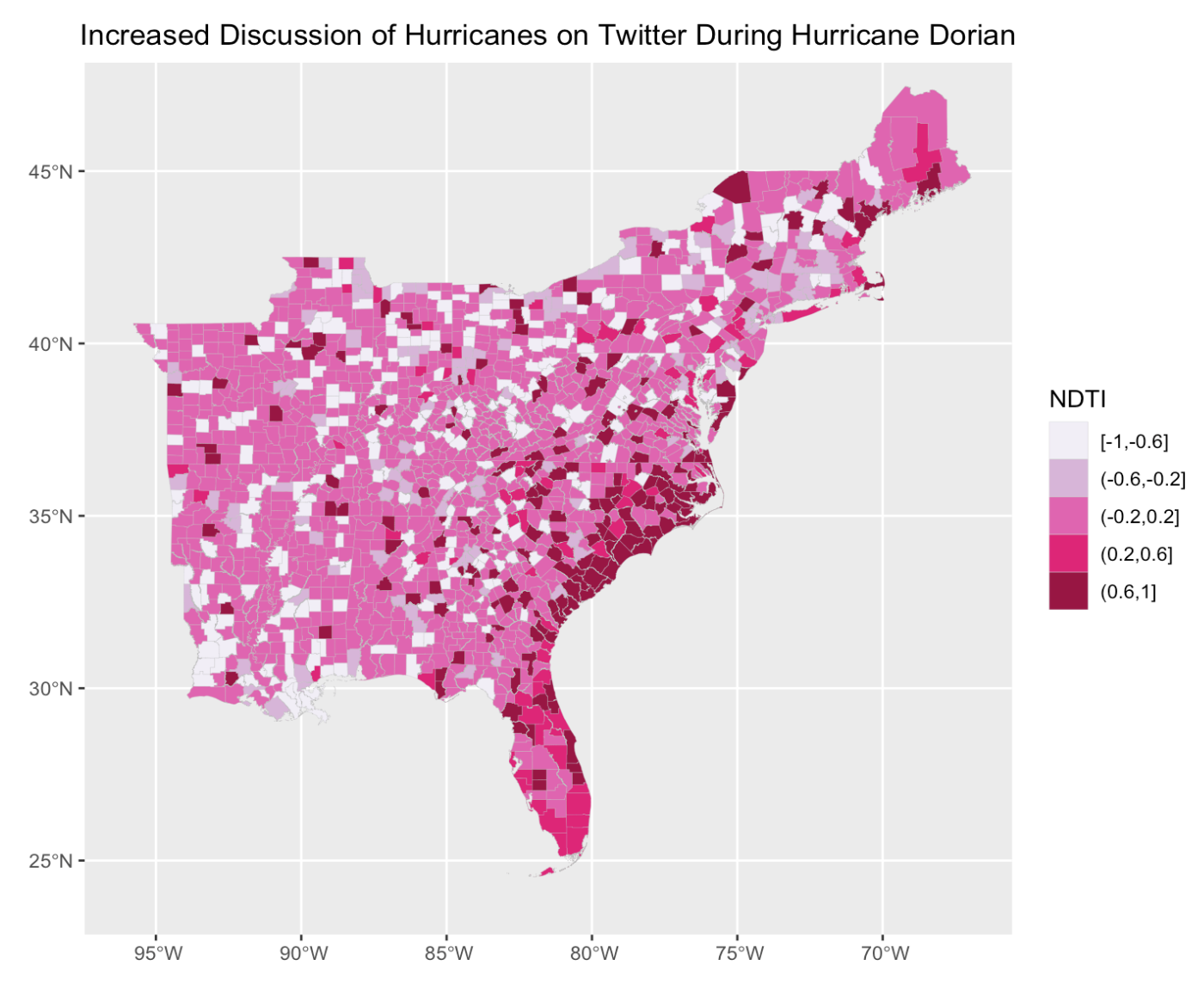

Hurricane Dorian

In the Hurricane Dorian analysis, some of uncertainty concerns were avoided by normalizing Twitter activity to baseline activity. The Normalized Difference Tweet Index (NDTI) was calculated as (Dorian - baseline)/(Dorian + baseline) (where Dorian indicates tweets that met the search criteria described above). It shows that hurricane-related activity was elevated in the areas that were affected by the storm, without being skewed by population. (However, it still doesn’t address the people who are not on Twitter but may have had concerns about Dorian.)

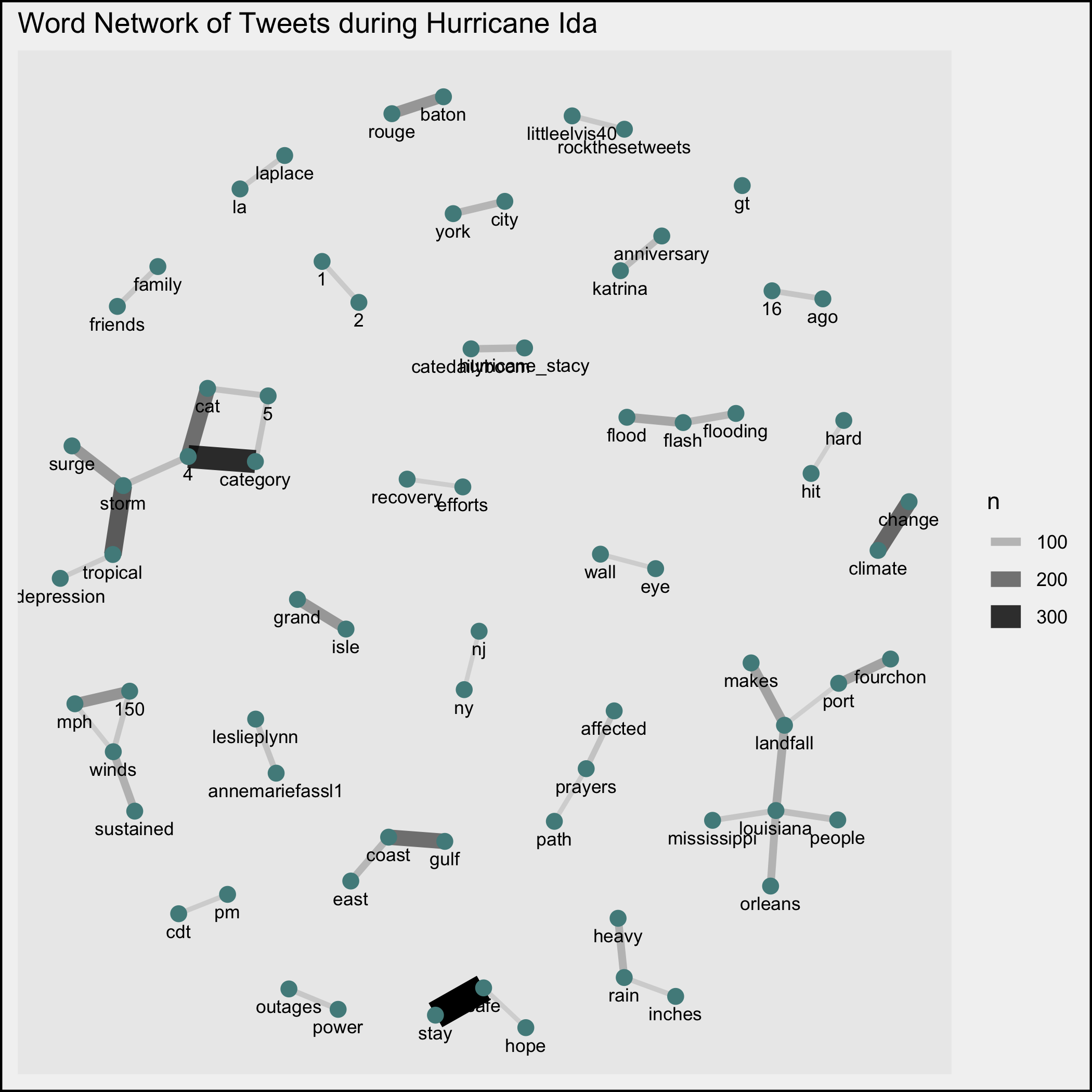

The tweets during Hurricane Dorian were not used to locate or track the storm, but rather to analyze the geographic and sociopolitical setting of the storm. No identifying information was published, but patterns within the online discourse were recorded via tweet word association. The network of paired words reveal common discourse around President Trump, Alabama, and NOAA (bottom left of figure). Though Twitter activity does not indicate increased concern in Alabama specifically as a result of Sharpiegate, the event provided an opportunity for commentary about the political context of the situation as well.

Reference

Crawford, K., and M. Finn. 2014. The limits of crisis data: analytical and ethical challenges of using social and mobile data to understand disasters. GeoJournal 80 (4):491–502. DOI: 10.1007/s10708-014-9597-z.